Hong Kong has no legislation regarding maximum and normal working hours. The average weekly working hours of full-time employees in Hong Kong is 49 hours. In Hong Kong, 70% of surveyed do not receive any overtime remuneration.

These show that people in Hong Kong concerns the working time issues. As Hong Kong implemented the minimum wage law in May 2011, the Chief Executive, Donald Tsang, of the Special Administrative Region pledged that the government will standardize working hours in Hong Kong. How an employee is paid depends on if the employee is non-exempt or exempt from minimum wage and/or overtime pay. The minimum wage and overtime pay are based on the hours worked each workweek and not by the number of hours worked each day or by the number of days worked regardless of the length of the pay period. As the length of the workweek gradually declined, political agitation for shorter hours seems to have waned for the next two decades.

However, immediately after the Civil War reductions in the length of the workweek reemerged as an important issue for organized labor. Roediger argues that many of the new ideas about shorter hours grew out of the abolitionists' critique of slavery — that long hours, like slavery, stunted aggregate demand in the economy. The hub of the newly launched movement was Boston and Grand Eight Hours Leagues sprang up around the country in 1865 and 1866. The leaders of the movement called the meeting of the first national organization to unite workers of different trades, the National Labor Union, which met in Baltimore in 1867. The passage of the state laws did foment action by workers — especially in Chicago where parades, a general strike, rioting and martial law ensued.

In only a few places did work hours fall after the passage of these laws. Many become disillusioned with the idea of using the government to promote shorter hours and by the late 1860s, efforts to push for a universal eight-hour day had been put on the back burner. Generally, business sector agrees that it is important to achieve work–life balance, but does not support a legislation to regulate working hours limit. They believe "standard working hours" is not the best way to achieve work–life balance and the root cause of the long working hours in Hong Kong is due to insufficient labor supply.

Full-time employees who stay with your company for at least 12 months aren't the only ones that might need an hourly breakdown. Some companies have full-time temporary or seasonal jobs, such as an accountant who hires additional workers to help during tax season. Other companies might have part-time workers who occasionally work full-time hours, such as getting 40 hours per week when filling in for sick employees.

Hours In A Full Time Work Week Depending on the reason you're calculating the hours, you might need to include these other forms of full-time hours as well. The long-term decline in the length of the workweek, in this view, has primarily been due to increased economic productivity, which has yielded higher wages for workers. Workers responded to this rise in potential income by "buying" more leisure time, as well as by buying more goods and services. In a recent survey, a sizeable majority of economic historians agreed with this view.

For example, roughly two-thirds of economic historians surveyed rejected the proposition that the efforts of labor unions were the primary cause of the drop in work hours before the Great Depression. Eastern European immigrants worked significantly longer than others, as did people in industries whose output varied considerably from season to season. High unionization and strike levels reduced hours to a small degree.

The average female employee worked about six and a half fewer hours per week in 1919 than did the average male employee. In city-level comparisons, state maximum hours laws appear to have had little affect on average work hours, once the influences of other factors have been taken into account. One possibility is that these laws were passed only after economic forces lowered the length of the workweek. Overall, in cities where wages were one percent higher, hours were about -0.13 to -0.05 percent lower. Again, this suggests that during the era of declining hours, workers were willing to use higher wages to "buy" shorter hours. The swift reduction of the workweek in the period around World War I has been extensively analyzed by Whaples .

His findings support the consensus that economic growth was the key to reduced work hours. He finds that the rapid economic expansion of the World War I period, which pushed up real wages by more than 18 percent between 1914 and 1919, explains about half of the drop in the length of the workweek. The reduction of immigration during the war was important, as it deprived employers of a group of workers who were willing to put in long hours, explaining about one-fifth of the hours decline. The rapid electrification of manufacturing seems also to have played an important role in reducing the workweek.

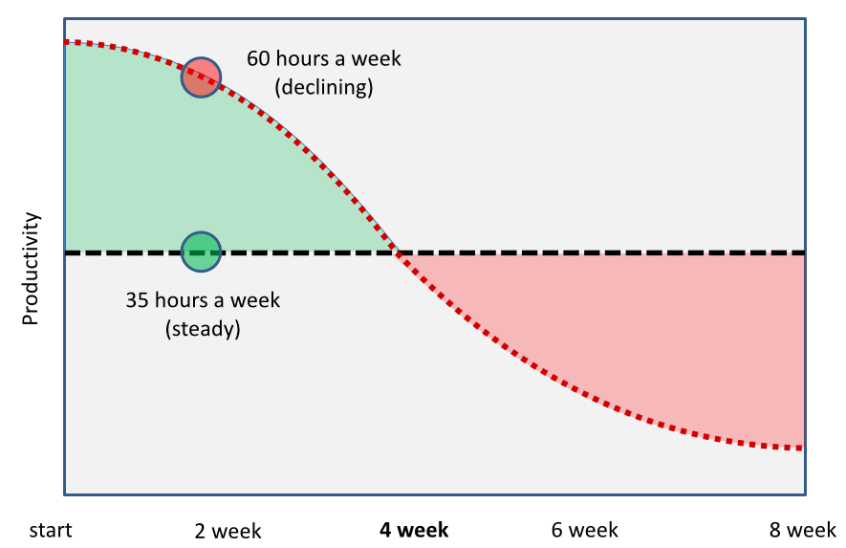

Increased unionization explains about one-seventh of the reduction, and federal and state legislation and policies that mandated reduced workweeks also had a noticeable role. The length of the workweek, like other labor market outcomes, is determined by the interaction of the supply and demand for labor. On the other hand, longer hours can bring reduced productivity due to worker fatigue and can bring worker demands for higher hourly wages to compensate for putting in long hours. If they set the workweek too high, workers may quit and few workers will be willing to work for them at a competitive wage rate. Thus, workers implicitly choose among a variety of jobs — some offering shorter hours and lower earnings, others offering longer hours and higher earnings.

Hunnicutt argues that an implicit deal was struck in the NIRA. Labor leaders were persuaded by NIRA Section 7a's provisions — which guaranteed union organization and collective bargaining — to support the NIRA rather than the Black-Connery Thirty-Hour Bill. Business, with the threat of thirty hours hanging over its head, fell raggedly into line. Despite a plan by NRA Administrator Hugh Johnson to make blanket provisions for a thirty-five hour workweek in all industry codes, by late August 1933, the momentum toward the thirty-hour week had dissipated.

About half of employees covered by NRA codes had their hours set at forty per week and nearly 40 percent had workweeks longer than forty hours. Many countries regulate the work week by law, such as stipulating minimum daily rest periods, annual holidays, and a maximum number of working hours per week. Working time may vary from person to person, often depending on economic conditions, location, culture, lifestyle choice, and the profitability of the individual's livelihood. For example, someone who is supporting children and paying a large mortgage might need to work more hours to meet basic costs of living than someone of the same earning power with lower housing costs.

Traditionally, employees who work 40 hours per week are considered to be full-time workers. However, many employers designate employees who work fewer hours as full-time workers. Companies determine the number of hours per week that are considered to be full-time. Full-time workers are likelier to receive benefits such as health insurance, sick pay and vacation time, and employer-provided retirement plans that part-time workers do not receive. Employers are not required to provide benefits to workers beyond those that are mandated by the law. Workers in New Jersey might wonder how many hours they need to work in a week to be considered to be full-time workers.

The Fair Labor Standards Act does not provide any laws that define full-time work. Instead, this determination depends on each company's policy and practices other than the requirements of the Affordable Care Act. The employment lawyers at Swartz Swidler can explain the industry standards in New Jersey and how they apply to full-time employees. The rules are the same for a large corporation or a small mom-and-pop business. C. Wage and Hour Act nor the federal Fair Labor Standards Act limit the amount of hours that an employee 18 years of age or older can be required to work either by the day, week, or number of days in a row. There are no limitations on how many hours an adult employee can be required to work regardless whether they are a salaried-exempt employee or a non-exempt employee.

The employer is only required to pay time and one-half overtime pay based on an employee's regular rate of pay for all hours worked in excess of 40 in a workweek to its non-exempt employees. There is no limit on the number of hours the adult employee may be required to work. Labor markets became very tight during World War I as the demand for workers soared and the unemployment rate plunged.

These forces put workers in a strong bargaining position, which they used to obtain shorter work schedules. The move to shorter hours was also pushed by the federal government, which gave unprecedented support to unionization. At the end of the war everyone wondered if organized labor would maintain its newfound power and the crucial test case was the steel industry. These abnormally long hours were the subject of much denunciation and a major issue in a strike that began in September 1919.

The strike failed (and organized labor's power receded during the 1920s), but four years later US Steel reduced its workday from twelve to eight hours. The move came after much arm-twisting by President Harding but its timing may be explained by immigration restrictions and the loss of immigrant workers who were willing to accept such long hours . Singapore enacts an 8-hour normal work day , a 44-hour normal working week, and a maximum 48-hour work week.

It is to note that if the employee works no more than five days a week, the employee's normal working day is 9-hour and the working week is 44 hours. Also, if the number of hours worked of the worker is less than 44 hours every alternate week, the 44-hour weekly limit may be exceeded in the other week. Yet, this is subjected to the pre-specification in the service contract and the maximum should not exceed 48 hours per week or 88 hours in any consecutive two week time. In addition, a shift worker can work up to 12 hours a day, provided that the average working hours per week do not exceed 44 over a consecutive 3-week time.

The overtime allowance per overtime hour must not be less than 1.5 times of the employee's hour basic rates. Under most circumstances, wage earners and lower-level employees may be legally required by an employer to work more than forty hours in a week; however, they are paid extra for the additional work. Many salaried workers and commission-paid sales staff are not covered by overtime laws.

These are generally called "exempt" positions, because they are exempt from federal and state laws that mandate extra pay for extra time worked. The rules are complex, but generally exempt workers are executives, professionals, or sales staff. For example, school teachers are not paid extra for working extra hours. Business owners and independent contractors are considered self-employed, and none of these laws apply to them.

The banner years for maximum hours legislation were right around 1910. This may have been partly a reaction to the Supreme Court's ruling upholding female-hours legislation in the Muller vs. Oregon case . The Court's rulings were not always completely consistent during this period, however. In 1898 the Court upheld a maximum eight-hour day for workmen in the hazardous industries of mining and smelting in Utah in Holden vs. Hardy. In Lochner vs. New York , it rejected as unconstitutional New York's ten-hour day for bakers, which was also adopted out of concerns for safety.

Several state courts, on the other hand, supported laws regulating the hours of men in only marginally hazardous work. By 1917, in Bunting vs. Oregon, the Supreme Court seemingly overturned the logic of the Lochner decision, supporting a state law that required overtime payment for all men working long hours. Men were allowed freedom of contract unless it could be proven that regulating their hours served a higher good for the population at large.

When Samuel Slater built the first textile mills in the U.S., "workers labored from sun up to sun down in summer and during the darkness of both morning and evening in the winter. Only attracted attention when they exceeded the common working day of twelve hours," according to Ware . This agitation was led by Sarah Bagley and the New England Female Labor Reform Association, which, beginning in 1845, petitioned the state legislature to intervene in the determination of hours. The petitions were followed by America's first-ever examination of labor conditions by a governmental investigating committee. However, these laws also specified that a contract freely entered into by employee and employer could set any length for the workweek.

Legislation passed by the federal government had a more direct, though limited effect. On March 31, 1840, President Martin Van Buren issued an executive order mandating a ten-hour day for all federal employees engaged in manual work. Being paid a salary does not exempt an employee from the minimum wage and/or overtime pay requirements. If an employee is paid a salary and is not paid time and one-half overtime pay for hours worked in excess of 40 in a workweek, then a determination must be made as to if the employee is a salaried-exempt employee or not.

The main categories to be a salaried-exempt employee are for executive employees, administrative employees, and professional employees who meet certain requirements. One of the general requirements is that the salaried-exempt employee must be paid a guaranteed salary of at least $684 a workweek , which would also be the promised rate of pay for the employee. It then does not matter how many hours the salaried-exempt employee works in a workweek as the guaranteed salary is pay for all hours worked in a workweek regardless of the number of hours worked.

For more details on the requirements for an employee to be a salaried-exempt employee, please review the Code of Federal Regulations 541, which the N.C. Full-time employees can be paid by the hour or on salary, which means they get the same amount of pay each week. Calculating the number of hours worked by each of your full-time employees helps you figure some of your financial liability. For example, having the correct number of hours allows you to assign an hourly wage to an employee that includes the cost of benefits such as health insurance and free parking.

After adding an employee's pay and the cost of his benefits together, you can divide that by the number of hours worked to see how much it costs you per hour to employ that person. Or, you might need to know how many hours were worked by all your employees combined to help set productivity goals. To do this, you must first know how many hours each employee worked. A new cadre of social scientists began to offer evidence that long hours produced health-threatening, productivity-reducing fatigue. This line of reasoning, advanced in the court brief of Louis Brandeis and Josephine Goldmark, was crucial in the Supreme Court's decision to support state regulation of women's hours in Muller vs. Oregon.

In addition, data relating to hours and output among British and American war workers during World War I helped convince some that long hours could be counterproductive. Businessmen, however, frequently attacked the shorter hours movement as merely a ploy to raise wages, since workers were generally willing to work overtime at higher wage rates. Because of changing definitions and data sources there does not exist a consistent series of workweek estimates covering the entire twentieth century. Despite differences among the series, there is a fairly consistent pattern, with weekly hours falling considerably during the first third of the century and much more slowly thereafter. In particular, hours fell strongly during the years surrounding World War I, so that by 1919 the eight-hour day had been won.

Owen's nonstudent-male series shows little trend after World War II, but the other series show a slow, but steady, decline in the length of the average workweek. Greis's two series are based on the average length of the workyear and adjust for paid vacations, holidays and other time-off. The last column is based on information reported by individuals in the decennial censuses and in the Current Population Survey of 1988. It may be the most accurate and representative series, as it is based entirely on the responses of individuals rather than employers.

Employers decide how many hours per week is full-time and part-time, and what the differences will be. Part-time employees are usually offered limited benefits and health care. For example, a part-time employee may not be eligible for paid time off, healthcare coverage, or paid sick leave.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.